Notes

Chapter Five: The Election Campaign

Campaigning in Unlevel Playing Fields:

A Conflict-Analysis Perspective

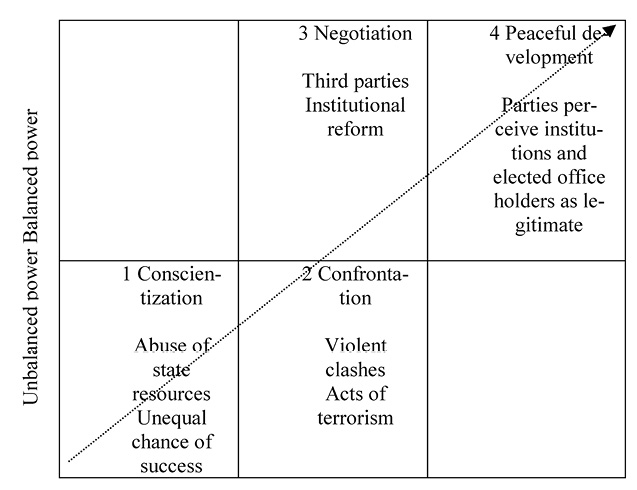

Most political parties in African elections have very limited capacity to reach their constituencies unless they can tap into incumbents’ financial assets and campaign means. Electoral contests between political actors competing for access to state resources in sub-Saharan Africa unfold in the context of highly asymmetric power relations between ruling and opposition parties. To analyse campaign violence in relation to peaceful outcomes, this chapter draws on a theoretical framework from the works of pioneering conflict-resolution scholars on the transformation of asymmetric conflicts (see Curle 1971; Lederach 1995). In a latent-conflict stage, incumbents maintain their hegemonic position by keeping underdogs down. In a phase of overt conflict, underdogs’ efforts to reverse power relations turn violent. Thus, electoral conflict breaks out when incumbents attempt to maintain their status quo and underdogs revolt against their unequal chance of success.

This study shows the goal-oriented nature of election violence, either as a coercive mechanism through which power holders achieve and sustain power or as a means of confronting asymmetric power relations by those who challenge the status quo. Campaign violence can be either spontaneous (e.g., clashes between supporters of political parties) or orchestrated (e.g., terror attacks to disrupt campaign events). Negotiation entails institutionalising mechanisms, such as conflict-management bodies, through which political parties can change the rules of the game to level the playing field, so that all contestants enjoy an equal chance of success in electoral contests. In this phase, incumbents’ political will to negotiate and implement electoral reforms to meet stakeholders and international donors’ demands intertwines with strategies to maintain their grip on power. Thus, electoral conflict only develops into peaceful relations when parties perceive institutions and elected office holders as legitimate.

Table 5.1. Transformation of Electoral Conflict

Unpeaceful relations / Peaceful relations

Source: Adapted original diagram by Ramsbotham et al. (2011, 13; original in Curle 1971 and Lederach 1995).

All African countries have ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), with the sole exception of Comoros and São Tomé and Príncipe (UN 1966). African constitutions and domestic legislation generally grant freedom of expression and assembly to individuals, political parties, and candidates. Hence, most African countries legally protect candidates’ access to the electorate and their equal chance of success (IDEA 2002). However, the extent to which freedom of expression and assembly is respected varies substantially depending on the country. Furthermore, as this study’s data illustrate, compliance with the principle of equal opportunity for contestants remains elusive because most African elections occur on notoriously unlevel playing fields. Candidates and party campaigners try to strengthen patron-client relations by convincing the electorate that they can address people’s concerns about employment, infrastructure, food, water, health, education, and so forth. Nonetheless, in the end, disputes among interest groups play out in election campaigns that incumbent candidates tend to dominate overwhelmingly through the use of state resources and corporate support.

Party Primaries: Survival of the Fittest

Ruling parties’ dominant role in African multiparty systems exacerbates the winner-take-all nature of their party primaries.50 In fact, several countries have experienced violent primaries of incumbent political parties, as candidates often perceive primaries as a zero-sum game and competition is fierce (Le Van et al. 2003; EISA 2005a). According to Posner and Young, the re-election rate of incumbent presidents was 86 percent between 1990 and the end of 2005 (2007, 131). While large political parties lay out formal procedures for the democratic election of candidates in compliance with domestic legislation, in practice patron-client relations and centralised structures of decision-making generally determine the outcome of party primaries.51 As Gazibo graphically describes, African political parties are an empty shell in which competition for power and resources unfolds, unrestrained by agreed-upon rules or internal disciplinary mechanisms, to ensure the political survival of the fittest, namely, those candidates enjoying a greater patronage network and greater resources (Gazibo 2006b; Randall and Svåsand 2002). Primaries may trigger bitter disputes and even defections when party leadership hand-picks parliamentary candidates and their selection is at odds with the will of local party cadres. Many irregularities, including physical attacks and threats, occur in a process that third parties and national and international observers usually do not witness (see, for instance, EUEOM 2002b; EISA 2005b, 2004b, 2007c; Gloppen et al. 2006; Khembo and Mcheka 2005; TEMCO 2006).

Some candidates defeated in party primaries defect to another party or possess enough social support and economic resources to run as independent candidates. In this regard, competition between candidates in primaries may continue during the electoral campaign period, and skirmishes between their supporters are not uncommon. Presidential candidates defeated in party primaries often become opposition leaders and, eventually, elected presidents.52 Yet, given the dominant position enjoyed by males in institutionalised political processes and cultural prejudices regarding women’s social role, female candidates competing in primaries are more exposed to gender discrimination and social harassment than their male competitors are (Lindberg 2004).

While electoral bodies are often criticised for refusing to regulate party primaries, the partisan nature of intraparty elections and the high stakes involved make it almost impossible for external actors to promote democratisation of decision-making processes within party structures. In the meantime, by provoking divisions and defections, intraparty disputes and undemocratic selection procedures not only weaken the parties’ chances of long-term survival but also taint the polity’s perception of political parties’ will to serve the nation.

Use of State Resources for Campaign Purposes

To influence voters’ choices, political parties set their campaign engines in motion several months before the government announces the official opening of the campaign period; parties do this by using state or private resources for public or covert actions, including vote buying, snatching of voters’ cards, or intimidation of candidates and their supporters. State workers, civil servants, and temporary employees are victims of bullying and other coercive practices intended to secure support for incumbent governments. Ruling political parties become powerful by building a support base that enables them to control the socioeconomic fabric of the country.53 The disparity in resources between the ruling party and other contestants undermines the democratic principle of equal chance of success.54 A statistical analysis of this project’s data exposes the relationship between asymmetric power relations and electoral conflict. While some elections unfold peacefully even though contestants do not compete on level playing fields, electoral violence rarely occurs when the playing field is level and parties fully endorse the process.

In electoral contests perceived as zero-sum games, unscrupulous contestants pursue election gains by any means; they may even mobilise violent groups to intimidate or eliminate their opponents. When economic and political agendas merge, elections become a playing field for criminal activities. In this regard, Nigeria provides an illustrative case study: violent attacks, abduction, assassination of political candidates, media defamation, inflammatory language in campaign events, and claims of widespread rigging mar electoral contests. Powerful patrons pull strings to get their candidates elected; to this end, they use a wide range of illicit practices in collusion, at times, with security personnel and electoral officers (Osiki 2010). Organised criminal gangs turn themselves into groups supporting politicians, to benefit from the country’s wealth pool. Thugs make use of physical violence, intimidation, and bribery to achieve their “political” goals (Ekong and Essien 2012).55 To thwart opposition efforts to achieve power, political entrepreneurs and high-ranked party members have also sponsored gangs in countries such as Kenya, Malawi, and Cameroon, by antagonising community groups and, in some cases, even inciting ethnic hatred (Kagwanja 2003; Dercon and Gutiérrez-Romero 2012).

Although the United Nations Human Rights Committee has specified that “reasonable limitations on campaign expenditure may be justified where this is necessary to ensure that the free choice of voters is not undermined or the democratic process distorted by the disproportionate expenditure on behalf of any candidate or party,” the use of state resources and private funding for election campaigning in sub-Saharan Africa has been barely regulated (UN HRC 1996). The African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance makes no reference to campaign financing, while the OAU/AU Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa mentions only that “all stakeholders in electoral contests shall publicly renounce the practice of granting favours, to the voting public for the purpose of influencing the outcome of elections” (OAU/AU 2002). Similarly, the Bamako declaration on democratic principles, endorsed by the state members of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), states that political parties should have access to state resources (OIF 2000). The lack of regulation by regional bodies reveals African governments’ reluctance to regulate campaign financing and the use of state resources.

Ruling parties use government and other state-owned vehicles, in breach of legal provisions and agreed-upon codes of conduct, to campaign and to transport their supporters to rallies (EUEOM 2000, 2007b, 2009b, 2010a; Commonwealth Observer Group 2001, 2002; Carter Center 2002, 2005, 2011c; NDI 2007b). At times, their registration plaques are removed or hidden. They use state premises and ministerial and local office buildings as logistical bases to store and distribute campaign materials.56 Civil servants who are party members actively participate in campaign events. State works are presented as successes of the ruling party, e.g., during campaign periods state television channels broadcast the opening of schools or hospitals by government officials.57 The literature on contemporary conflict describes the use of development and humanitarian aid as a tool of war. Perhaps less well known is the extent to which governments use the distribution of aid to vulnerable communities as a political campaign tool. Campaigners distribute staple food, rice, cereals, seeds, fertilisers, or even construction materials in poverty-stricken areas.58 While the political prerogatives of traditional authorities in most African states were broadly curtailed when the colonial indirect-rule system ended, chiefs in rural areas politically influence their communities either by advocating for “the government of the day” or by expressing their support for other political actors with whom they maintain close ties.

The blurring of divisions between the state and the ruling party paves the way for the use of public security forces to intimidate political opponents.59 The pyramidal structure of African ruling parties reproduces the governance layers of their highly centralised presidential systems. Parties generally develop a hierarchical modus operandi that enables the higher ranks to gather information and give instructions to party cadres countrywide. Parties set up cells that are parallel to the state’s administrative structures, on the village, municipal, provincial, regional, and state levels, for social and political organisation. The mass availability of mobile communication has facilitated communication between party officials based in distant locations.

Intimidation is a cost-effective tool of political control since it relies on counterfactuals i.e., “what could happen to you if you don’t do what I ask for.” When ruling parties remain in power for decades and the distinction between party and state structures is elusive, citizens learn to operate within a confined spectrum of political freedoms. Self-censorship is a pervasive effect of political cultures that rely on clientelism and, to some extent, intimidation to maintain the status quo. The psychosocial sequels derived from instances of intimidation linger over time, and today’s reprisals against voters influence the electorate’s political behaviour decades later.

Ruling parties’ struggle for power by any means leads to the militarisation of election campaigns, allegedly for the sake of national security.60 Across Africa, people often perceive the excessive use of police force against demonstrators and political activists as an abuse of power by incumbents to dissuade voters from supporting opposition parties.61 Ruling parties tend to securitize election campaigns by portraying their challengers as lovers of chaos aiming to disrupt peace and breach social order. In contrast, ruling parties “sell” continuity as the only viable option for maintaining peace and stability.62 In turn, in this context cunning opposition leaders point the finger (with justification or not) at incumbent parties for orchestrating repressive state campaigns to thwart their electoral chances, to rally popular support and win sympathy from the international community.

Voter Education as a Campaign Strategy

Election laws and regulations pay insufficient attention to political parties’ rights and obligations regarding voter education. Namibia’s Electoral Act specifies that political parties do not require accreditation from the Electoral Commission of Namibia63 to conduct voter education, while in South Africa political parties are expected to run voter-education workshops (Electoral Commission of South Africa 2014). In practice, in the absence of adequate public resources for voter educators to reach out to villagers countrywide, resourceful political parties adopt a proactive voter-education role across Africa as part of their broader campaign strategy. Campaign teams enlighten voters on polling procedures while conducting door-to-door campaigning or public meetings (see, for example, EUEOM 2011b). Their party activists use ballot-paper samples with a cross ticked or a fingerprint mark on the box of the candidate or party providing the voter education. This way, enlightening and adamant “party educators” can influence illiterate voters who may not clearly understand multiparty democracy or their political rights as citizens. Hence, affluent political parties that are able to conduct partisan voter education enjoy a comparative electoral advantage over poorer parties.

Politicians eager to keep power by any means regard citizens not as subjects to represent but as their political subjects. Civic-education projects conducted by state agencies or NGOs help to raise social awareness of citizens’ rights and democratic principles; however, information more easily reaches literate citizens, while uneducated ones remain more vulnerable to abuses by politicians keen on twisting the rules of the game to their advantage. Most methodologies assessing democracy focus on comparative analysis of codified data sets but tend to neglect country-specific qualitative data and the extent to which political cultures influence decision-making (McHenry 2000). Democracy indices fail to identify, for instance, the extent to which open or milder forms of intimidation shape political behaviour and determine the political choices of vulnerable sectors of society.64

The Role of Religious Authorities in Election Campaigns

In general terms, religious authorities play a committed, conscious role by sensitising their worshippers in churches and mosques on the need to elect political leaders who will try to implement their campaign agendas for the community’s benefit. Religious associations, networks, federations, and councils not only carry out wide-reaching civic and voter-education campaigns but also observe electoral processes and monitor human rights throughout Africa.

Although religion occupies a central place in the political debate of most African states, observer reports do not provide significant evidence on religious authorities’ role in election campaigns since observation focuses mainly on secular activities. In East Africa, some observation reports have described religious authorities’ attempts to influence believers’ electoral behaviour. A good case in point is the late president of Zambia, Michael Sata. He was a long-standing opposition leader and a devoted member of the politically influential Zambian Roman Catholic Church. Sata allegedly received support from many outspoken Catholic priests who relayed messages for political change to churchgoers (Sishuwa 2011). One supporter was Father Frank Bwalya, who staged a campaign of red cards to protest the ruling MMD party’s involvement in corrupt practices (Paget 2014). After he was proclaimed president, Sata expressed openly his gratefulness to the Catholic Church: “You have been carrying this cross for me to ascend to the Presidency for the past 10 years and one month. There are times when you were called all sorts of names. When our colleagues brought the name of the Catholic Church into disrepute, you stood by me” (Chambwa and Samulela 2011).

A merging of presidential and church agendas became apparent in Madagascar when Marc Ravalomanana, a successful businessman, took office as president in 2002. At the time, he was vice-president of the Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar (FJKM), the largest Protestant church in the country. Although the Catholic Church and other Protestant churches initially supported his candidacy during the 2002 political crisis, Ravalomanana’s policies eventually antagonised the Catholic Church and the Muslim minority claiming that he was furthering FJKM’s political agenda (Hogg 2007; Africa Confidential 2010, 9). In the presidential elections of 2013, religion remained a relevant factor in party politics, and some churches continued to offer behind-the-curtain political support for candidates, even though Ravalomanana no longer contested (Ravelontsalama 2013).

Although Tanzania has a long tradition of peaceful coexistence among religions, some politicians have also attempted to exploit religious fault lines and socioeconomic grievances for partisan purposes. In turn, religious representatives have accused one another of partisan involvement.65 Before the 2010 general elections, the Roman Catholic Church published a pastoral letter in 2009 to sensitise worshippers on the need to choose leaders who rejected corruption. Some supporters of the ruling CCM party and its incumbent presidential candidate, Jakaya Kikwete, a Muslim, perceived this as a way to support the opposition party CHADEMA, since CCM has been in power since the country’s independence and is therefore the only party that could be accused of corruption (Gahnström 2012). For its part, a few weeks later, the Political Committee of the Council of Muslim Clerics published its own election guidelines that cautioned against the Catholic Church’s influence on voters’ choice and stressed that candidates should be elected by the free will of the people (U.S. Department of State 2010; The Guardian 2009).

Unbalanced Media Reporting

An analysis of the relationship between the use of state resources and unbalanced media reporting provides further evidence of incumbents’ tools of political pressure. In general, African states lack national regulation of political parties’ access to public media, in contrast to their regional commitments.66 This study’s data confirm that in most African elections held during the 2000–2011 period, election observers reported media biases in favour of incumbent candidates. Ruling parties’ use of state resources to campaign correlates strongly with unbalanced media reporting.67 Governments control information broadcasted by state media as a way to influence electoral outcomes while restricting the role of independent media. Besides allocating electoral campaign slots to all candidates following domestic campaign legislation, ruling parties use state-owned media (television, radio, or newspapers) to disseminate news showing the positive aspects of their policies and government works in different areas (infrastructure, health, education, agriculture, and so forth).

While media outlets have generally played a positive, peace-building role in post-conflict societies by promoting the values of democracy and peaceful coexistence, the specialised literature has paid scant attention to media’s impact on fostering political violence, with some exceptions, such as studies on the dissemination of hate speech across the airwaves prior to and during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.68 Media outlets are used as a political tool to disqualify or denigrate opponents in pursuit of zero-sum outcomes, by antagonising political contestants and relaying a Manichaean dichotomy of good versus evil. Although most journalists commit to ethical standards of reporting and comply with media codes of conduct and best practices, unscrupulous reporters misreport and defame to show political support or in exchange for financial retribution and kickbacks. As revealed recently in francophone West Africa, misreporting carries tragic consequences. In Côte d’Ivoire, the UN and Human Rights Watch accused Radiodiffusion Télévision Ivoirian (RTI) and pro-Gbagbo campaigners of inciting intolerance and violence against opposition and international stakeholders during the 2010 election campaign (Straus 2011). In Guinea Conakry, media outlets reported that 120 supporters of the Rassemblement du Peuple Guinée (RPG) who fell sick during the final RPG campaign rally had been poisoned. The dissemination of these unproven allegations triggered an outbreak of violence against supporters of the Union des Forces Démocratiques de Guinée (UFDG) in Upper Guinea and Forest Region in October 2010 (Carter Center 2010a).

Obstacles to freedom of expression thwart contestants’ political right to convey their message to the electorate, while hampering citizens’ access to valuable information about their electoral choices. Censorship and libel laws still hamper freedom of expression in several countries, while intimidation and harassment against journalists expressing independent views have also been reported across the continent (Carter Center 2002, 2010b; Commonwealth Observer Group 2001, 2005a, 2006b 2007; Commonwealth Expert Team 2004; EUEOM 2003c, 2011c; OIF 2003, 2005a; Vollan 2005). From 2002 to 2012, according to Reporters Without Borders, eighty victims were killed because of their activities as journalists in sub-Saharan Africa. Most of these fatalities were reported since 2007, and more than half (forty-six) died in Somalia (Reporters Without Borders n.d.). Besides known, politically motivated murders of journalists, such as the killing on 8 July 2006 of freelance journalist Bapuwa Mwamba, who had criticised the transitional Congolese government, or the assassination in December 2004 of Deyda Hydara, editor of a Gambian newspaper critical of the government, many cases of intimidation or attacks against journalists are not reported given that self-censorship remains common among African journalists covering elections (EISA 2010c; EUEOM Angola 2008; NDI 2003). Constraints on media freedom undermine the credibility of polls by denying an equal chance to all contestants and, thus, helping to maintain an unlevel playing field.

Towards Peaceful Outcomes: Concluding

Remarks and Lessons Learned

Despite domestic and international observer groups’ monitoring efforts and recurring recommendations to curtail incumbent governments’ illicit use of state resources, illegal campaign activities occur overtly and often shamelessly in the absence of sound regulation or functioning mechanisms to uphold the rule of law. While violence can result from reciprocal factors that can be either endogenous or exogenous to the electoral process, election disputes always arise in the context of unlevel playing fields, which underscores the urgency of addressing this issue in order to prevent electoral conflict.

Dealing peacefully with electoral conflict requires effective regulatory measures to balance the political playing field as well as support for independent rule-of-law institutions ensuring that all contestants have an equal chance and that spoilers are held to account. Nevertheless, the winner-take-all nature of African elections, as a means of attaining political power and access to economic resources, makes this goal hardly achievable unless internally driven changes address the exogenous causes of conflict, such as poverty, inequality, and corruption (Bayart 2009).

Across Africa, political parties’ and candidates’ endorsement of codes of conducts for campaigning in democratic elections has contributed to the peaceful outcome of campaign activities, by making party cadres and supporters aware of the common benefits of complying with legal frameworks and campaign procedures. However, parties and candidates are not always legally bound to comply with codes of conduct; and even if they are, enforcement mechanisms in regulatory frameworks to prosecute spoilers are not efficiently applied or are used in a partisan way to safeguard incumbents’ interests.

50. See the concept of the dominant party system put forward by Sartori 1976, 121–24 and Bogaards 2000.

51. Govea and Holm (1998) find evidence that most successions within political parties in Africa tend to be unregulated.

52. After several defeats, the Patriotic Front (PF) leader Michael Sata won the Zambian presidential elections held in 2011. In the 1990s, Michael Sata had served as minister of various portfolios of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) government in Zambia. In 2001, when President Chiluba nominated Levy Mwanawasa as the MMD’s presidential candidate for the 2001 election, Sata left the MMD and set up the PF. Mwai Kibaki, former executive of the Kenya African National Union who served as vice-president under Daniel arap Moi’s presidency of Kenya, was elected president in 2002, leading the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC). Macky Sall, former Prime Minister of Senegal and subsequently President of the National Assembly under President Abdoulaye Wade, left the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS) at the end of 2008 and founded his own party, after coming into conflict with Wade. Sall received support from other opposition candidates who contested in the first round of the 2012 presidential election and was able to defeat Wade in the second round.

53. Observer groups have widely reported incumbents’ use of state resources to campaign: the Commonwealth Observer Group 2001; Masamba et al. 2002; EISA 2006a, 2007c; EUEOM Angola 2008; Namibia NGO Forum and SADC Council of NGOs 2009; SUNDE/SUGDE 2011.

54. In 2011, the ruling CPDM party in Cameroon bought all billboard spaces available for campaign purposes; see the Commonwealth Expert Team 2011. Likewise, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the candidate Joseph Kabila largely dominated the public space through billboards and access to media; see EUEOM 2007c.

55. See also data gathered by reports from international and national observation groups on assassinations of Nigerian candidates and well-known politicians in recent decades.

56. Governors’ offices and other premises were used as electoral headquarters and rally points for supporters in most states during the 2003 elections in Nigeria. In some cases, the local government administrative structure was fully integrated into the incumbent candidate’s campaign machinery; see EUEOM 2003b and 2011a. In Togo, EU observers reported on the presidential use of state resources for Faure Gnassingbé’s campaign (public media, administrative staff, local officials, etc.) and security officials’ logistics to transport campaign materials of the ruling RPT party. RPT party cadres and civil servants distributed rice at lower prices than market rate, the so-called Riz Faure; see EUEOM 2010g.

57. See, for example, the opening of educational and health facilities during the campaign period by candidate Ahmed Haroun in Southern Kordofan, in the Carter Center 2001.

58. The Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) used agricultural support programmes to try to influence the rural population (Commonwealth Observer Group 2006c).

59. The EUEOM (2010b) reported pre-trial detention and/or arbitrary arrests of opposition supporters and candidates in Ethiopia.

60. In Zimbabwe, when Zanu-PF lost part of its support base in 2002, numerous resources were mobilised during the election campaign, such as the setting up of 150 militia bases, the appointment of prominent military officers to head the Electoral Supervisory Commission, and numerous attacks against opposition leaders or their supporters; see Sachikonye 2002; national and international election observation missions reported violent attacks, clashes, and a climate of intimidation during the Zimbabwean polls held in 2000, 2002, 2005, and 2008.

61. Cases in point: on 28 September 2009, there was a large pro-democracy rally in the national stadium of Conakry as part of protests demanding that a Guinean military ruler not contest as a candidate in the presidential election. Security forces locked thousands of protesters in the stadium and opened fire on the crowd. It is estimated than over 150 opposition protesters were killed, many were injured, and several women were raped. Camara himself was seriously wounded by his aide-de-camp some weeks later amidst bitter disputes over his responsibility for the massacre; see the Carter Center 2010a; Tanzanian police used teargas against opposition rallies; see EISA 2006b. Campaign restrictions in Uganda were selectively enforced; see the Commonwealth Observer Group 2006b; Southern Sudan’s police allegedly harassed pro-unity activists; see EUEOM 2010f and the Carter Center 2010b; on the intimidation of the population in the Togolese hinterland by military officials, see OIF 2005c.

62. On securitisation theory see Buzan et al. 1998.

63. Section 47D of the Electoral Amendment Act, Act 7 of 2009 in the Namibia NGO Forum and SADC Council of NGOs 2009. Furthermore, article 54 of Electoral Act No. 5 of 2014 specifies that “A registered political party or registered organisation may provide voter and civic education to its members, supporters and sympathisers in respect of any election or referendum…”

64. During the seven days’ poll of the referendum on Southern Sudanese independence, voters were not only summoned by local authorities in some instances, but threatening messages were sent out through social media. The following is an extract from a radio interview on Yambio FM to a senior political advisor to the state governor on behalf of Sudan’s People Liberation Movement (SPLM) authorities: “Even if you are one person who has voted for Unity we shall know you. Even if you are three hundred or more, if you have not voted we shall know you”; see EUEOM 2010f.

65. In the same vein, in Malawi, long-term election observers reported priests’ concerns regarding the role of the wealthy Asian community in promoting the Muslim political power base in the parliamentary and presidential elections of 2004. See EUEOM 2004.

66. The African Union Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa stipulates that “every candidate and political party shall respect the impartiality of the public media”; see article 11 of section IV on Elections: Rights and Obligations of The African Union Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa, AHG/Decl.1 (XXXVIII) (AU 2002); the SADC’s Norms and Standards for Elections in the SADC Region underline that states need to guarantee contesting parties and candidates fair and equitable access to state-controlled media during elections (SADC 2001a).

67. Correlation of the variables “Reported Use of State Resources Y/N” and “Unbalanced Media Y/N,” drawn from this project’s research database, which includes 234 documents and covers 115 African electoral processes between 2000 and 2011, yields a coefficient of 0.64.

68. For literature on African conflict and the media, see Price and Thompson 2002; Khan 1998; and Thompson 2007.