2

Migration

Eastern Shore planters shamelessly sold slaves for profit, and then complained bitterly when free African Americans picked up and moved for their own economic gain. As early as 1797 some white residents of Talbot County urged the Maryland legislature to prohibit “manumitted slaves & their descendents to run about from county to county or to leave that in which their Manumitter resided unless to quit the State entirely.”1 White frustration with black migration waxed and waned through the early nineteenth century, but it was a sentiment that Maryland planters shared with planters in the postemancipation British Caribbean and later the post–Civil War South. In the 1860s and 1870s Maryland planters would again complain of chronic labor shortages as thousands of emancipated African Americans left their plantations for small towns and large cities. In both eras planters rebuked free African Americans for their “vagrancy” and then looked to the legislature to fix the new labor market to their advantage.

African Americans, meanwhile, insisted on exercising their rights to mobility. Manumitted and freeborn African Americans in the early republic understood just as well as later generations of emancipated people that mobility, the right to move or not to move, was integral to the definition of freedom. African American migration was also purposeful. People did not run about from county to county because they could, as the Talbot petitioners suggested. They moved because the expanding economy had created a heavy and steady demand for labor in Philadelphia and Baltimore and on grain farms across Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. African American wage laborers migrated to take advantage of these employment opportunities. Some fled the countryside, never intending to return, while others engaged in planned, short-term migration. Some men and women were perpetually in motion, traveling back and forth between urban employment and rural family dwellings. The Maryland government largely ignored the Talbot County petitioners and others who wanted to put limits on African American mobility. With such a steady demand for labor in all sectors of the economy, the state wanted to facilitate migration for work, not prevent it.

To varying degrees, every slaveholding state put limits on the mobility of free African Americans, because slaveholders insisted on such regulations as a matter of public safety. American slaveholders charged that free African Americans posed a threat to public safety, but what they really meant was that black freedom encouraged insolence among slaves. They argued that state authorities should strictly regulate the mobility of free African Americans as a preventative measure against slave rebellion. In theory, the threat of slave unrest grew in proportion with the free African American population, but even in the 1830s Maryland slaveholders did not behave as if they feared for their lives. They acted with great confidence that slave rebellion was not a problem of theirs. This certitude of their own safety stemmed partly from demographics. Maryland whites outnumbered all free and enslaved African Americans two to one by 1830, a population advantage that heightened the confidence of white Marylanders that a revolt would never get past the planning stages.2 It also stemmed from their peculiar history. In more than 150 years of slaveholding, Maryland slaveholders had never contended with a prolonged slave rebellion that extended beyond the boundaries of a single plantation. Slave traders carried enslaved Africans to Maryland in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but the colony never experienced a rebellion like those in New York (1712 and 1741) or South Carolina (1739). In the nineteenth century, slave traders carried African Americans from their ancestral homes in Maryland to an uncertain fate in the cotton growing states, but the slaves did not rebel. The abolition of slavery in Pennsylvania (1780) did not result in any armed rebellion, although it certainly encouraged slaves to run away. Maryland slaves did not rebel in response to the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), and although Baltimore received refugees from that island, Baltimore never contended with an uprising of Saint-Domingue refugees as New Orleans did in 1811. Similarly, Gabriel’s Rebellion (1800) in Richmond, Virginia, did not incite a similar uprising in Baltimore, even though the fast-growing population of both black and white artisans who lived and worked in Baltimore would have identified with Gabriel’s ideology.

But if rebellion seemed a remote possibility, slave escape was an inveterate problem for Maryland slaveholders. During the American Revolution, Maryland slaveholders lost inestimable numbers of slaves to the British Navy that patrolled Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Even more worrisome to Eastern Shore slaveholders was the boldness with which some escaped slaves returned at the head of British raiding parties, which looted coastal plantations and lured away additional escapees.3 History repeated itself during the War of 1812. Great Britain’s attacks on Baltimore and the District of Columbia terrified the whites, while slaves greeted the British as liberators. Once again, unknown numbers of Maryland slaves escaped to the British fleet, and some returned to fight alongside the British in 1814.4 Slaves would continue to rely on the waterways for escape well after the British evacuated the United States. In peacetime, escaping slaves joined the crews of American vessels bound for the free states, the Caribbean, and Europe. The problem of slave escape via the waterways was sufficiently vexing that in 1825 the Maryland legislature passed a law that required ship captains to keep a register of all the African Americans on board and authorized local authorities to search ships without a warrant for escaping slaves. Virginia adopted similar legislation in the 1850s, allowing for the search of all northward-bound vessels.5

In the 1790s Maryland slaveholders discovered that for escaping slaves peacetime prosperity provided as good a cover as wartime chaos. Economic expansion had created an unanticipated labor shortage across Maryland, and the heavy demand for laborers in all industries incentivized escape. Eastern Shore planters needed cheap and temporary labor, but so did a great many other farmers throughout Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. In Baltimore, Philadelphia, Wilmington, and the District of Columbia, merchants, manufacturers, and shipbuilders also needed more labor than they could readily find. Even the state of Maryland needed a continuous labor supply to build and maintain the transportation infrastructure (roads, canals, and Baltimore Harbor) that would connect agricultural regions with Baltimore. Slaveholders soon discovered that employers who needed cheap and temporary laborers did not ask too many questions when an unfamiliar African American came to town looking for work. Eastern Shore planters complained bitterly about Delaware and Pennsylvania farmers who employed runaways. In 1797 planter James Hollyday of Kent County sought assistance in recovering Dick, a slave who had escaped to Pennsylvania and was rumored to live among Quakers. In a letter to William Tilghman, Hollyday wrote that he had reason to believe that a Pennsylvania Quaker had hired Dick to care for his horses and drive his carriage. Seeking Tilghman’s assistance in tracking down Dick, Hollyday declared he would “spare no pains or expense to get the fellow again” because Dick “keeps up a correspondence with my Negroes, and is enticing them away from me.” He further charged that greed more than charity motivated the Quakers who harbored his escaped slaves. After all, “runaway Negroes who want concealment, protection and a pass undoubtedly do work cheap.”6 In response to this very concern, the Maryland legislature adopted six resolutions between 1798 and 1826 that urged the Pennsylvania and Delaware legislatures to punish farmers who harbored and hired runaways.

Even as William Tilghman maneuvered to recover his runaway, many other slaveholders made the choice to release their slaves into this expanding labor market. Perhaps the slaves were underemployed at home, or perhaps the slaveholders could not find a suitable employer to hire the slave on an annual contract. For whatever reason, more slaveholders were releasing their slaves into the community to hire themselves out. It was a practice that bothered the government, which passed a series of laws designed to discourage slaveholders from allowing their slaves to hire themselves without a contract. While not opposed to slave hiring, the state clearly preferred one-year contracts negotiated between slaveholders and prospective employers because contracts presumed continual employment and assured white Marylanders that these slaves remained under some white person’s authority. By contrast, slaves who hired themselves out were temporarily masterless. As early as 1787 the state imposed a fine on slaveholders who permitted their slaves to hire themselves out. Nine years later, the state required slaveholders to post a bond with local authorities when they let slaves hire themselves out. In 1823 the Maryland General Assembly passed legislation that authorized select Eastern Shore constables to arrest any slaves found working without a contract and then to hire them out for the duration of the year. The legislature added an important exception to these laws: it permitted slaves to move without threat of arrest “during twenty days in harvest time.”7

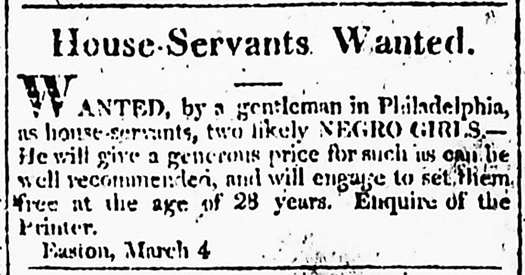

Figure 2. House Servants Wanted, 1817. A Philadelphia employer proposes to hire two term slaves from Maryland. The advertisement illustrates the scope of the labor market. March 4, 1817, Republican Star, or Eastern Shore General Advertiser. Courtesy of University of Vermont.

Gradual manumission only complicated the efforts of the government to manage the mobility of unfree laborers in an otherwise unregulated labor market. With more term slaves, manumitted slaves, and freeborn African Americans entering the workforce every day and moving from plantation to plantation, country to city, and even between states, Maryland whites needed a system to distinguish legitimately free workers from enslaved workers earning wages for slaveholders.

Certificates of Freedom provided one potential solution. Popularly known as “freedom papers,” the Certificates of Freedom had their origins in a 1796 law that required former slaves to carry documentation that identified them as legally free. Certificates included details about the manumitted person’s sex, height, age, skin tone, scars, and deformities, as well as a cursory explanation of how the bearer obtained freedom. Beginning in 1808, even freeborn African Americans could apply for certificates.8 Freedom certificates offered a convenience to both employers and free African American employees. If nothing else, the certificates clarified for employers which African American migrants were legitimate freedmen. But even certificates were not the final word on freedom. Later, the Maryland legislature pronounced that sheriffs could not detain a migrating African American on suspicion of being a runaway without just cause.9 In other words, local authorities should presume that even those African Americans traveling without freedom papers were free African American migrant workers, not runaway slaves.

Over the centuries a mythology has developed around these “freedom papers.” We have long assumed that because the legislature required former slaves to register with their local courts, free African Americans did so. We have also assumed that courts used the registration-certification process to monitor and restrain African American mobility. Moreover, it was believed that free African Americans who never applied for freedom papers or lost their papers or had their papers stolen or destroyed faced certain re-enslavement at the hands of unscrupulous white men. Frederick Douglass suggested as much in his autobiography. Douglass insisted that “cases have been known, where freemen have been called upon to show their papers, by a pack of ruffians—and, on the presentation of the papers, the ruffians have torn them up, and seized their victim, and sold him to a life of endless bondage.”10 In other words, freedom papers were all that separated freedmen from slaves, and any free African American who valued his freedom would not dare leave his home, never mind his community, without his freedom papers safely tucked in his pocket.

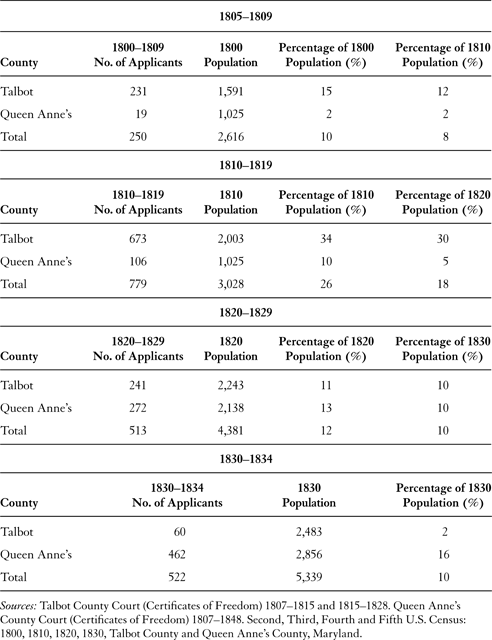

As Douglass’s account implies, and every free African American knew, a piece of paper would not deter a kidnapper who was determined to steal and sell a man into slavery. If freedom papers protected African Americans from abduction, then one would expect that children, who were most vulnerable to kidnapping, would carry certificates in greater numbers than the elderly or others who were less vulnerable.11 This was not the case. In Talbot and Queen Anne’s counties only seventy children sixteen years or younger applied for certificates before 1832 (less than 3% of all certificate bearers). Free African Americans of all ages disregarded the General Assembly’s mandate. Only a fraction of manumitted or freeborn African Americans in Maryland ever applied for freedom certificates (table 2.1). In 1810 fewer than 9 percent of free African Americans in Baltimore applied to the Baltimore County Court for freedom certificates. By 1820 perhaps as few as 4 percent of free African Americans in Baltimore carried certificates.12 On the Eastern Shore more freedmen applied for the certificates, but even as late as 1830, twenty-five years after the legislature standardized the certificates, only 10 percent of the free African Americans in either Queen Anne’s or Talbot counties applied for them. In 1805, the first year county clerks recorded freedom certificates in the public record, only one manumitted slave appeared before the Talbot clerk.13 Twenty-five years later, only ten African Americans (three women and seven men) applied for certificates. In Talbot County three times as many free African Americans applied for certificates between 1810 and 1819 as had done so in the previous decade. Sixty-seven percent of the Talbot County applicants appeared before the court clerk between 1815 and 1819, and more freedmen applied for certificates in 1815 than in any other year before 1834.14 Similarly, in Queen Anne’s County the number of applicants for freedom certificates doubled after 1820. Before 1819 only 125 freedmen applied for certificates, but between 1820 and 1829, 272 people received certificates. Although the Queen Anne’s County Court issued an average of eighteen certificates annually before 1829, the court issued seventy-two certificates in 1826, forty-nine in 1827, and sixty-nine in 1828.

Table 2.1 Applicants for Certificates of Freedom as a percentage of whole free black populations, Queen Anne’s and Talbot counties, 1805–1834

In 1793 the Virginia General Assembly adopted similar legislation with similar outcomes. In Fairfax County, which claimed 311 free African American residents in 1830, only 95 free African Americans registered in eight years. In Campbell County, south of Lynchburg, only 287 free African Americans registered in forty years. In Amherst County, north of Lynchburg, only a third of the free African American population ever registered before 1860. Even in the aftermath of Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831), when African Americans would have been most vulnerable to abuse and the state was extraordinarily concerned with public safety, clerks at the Fairfax County Court issued 177 certificates in two months, and these certificates represented a full 40 percent of the total number of certificates issued between 1822 and 1835.15 The lack of compliance is surprising considering that Virginia law empowered local authorities to fine freedmen who could not present their papers on demand, and the state required reregistration every three years.16 Delaware did not require free African Americans to apply for certificates at all until 1826.17

Whatever the intent of the registration and certification laws, it is clear that by the 1810s, free African Americans in Maryland had adopted freedom papers for their own purposes. Free African Americans did not apply because they were required to do so or because they thought that the certificates would protect their freedom. They filed for certificates because the papers facilitated migration and thereby created opportunities. Men and women obtained certificates when they expected to go among strangers in unfamiliar communities.

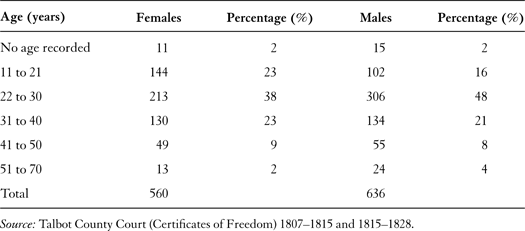

In early national Maryland freedom papers functioned like contemporary green cards, identifying free African Americans as legitimate free workers, eligible for employment anywhere. As Thomas Cole’s 1794 certificate stated, he was a freedman and permitted “to engage in what work or business he pleases.”18 Predictably, the overwhelming majority of certificate applicants who appeared in Eastern Shore county courts were young, able-bodied, and single. Nearly 60 percent of applicants from Queen Anne’s and Talbot counties were under thirty years old: 12 percent were teenagers and 47 percent were between twenty and twenty-nine years old. Most of the twenty-year-olds were not heads of households but unwed young people who often arrived at the court clerk’s office accompanied by a sibling. The members of the Pipes and Maccary households exemplify this trend. Between 1814 and 1818, four of Isaac and Memory Maccary’s adult children applied for freedom certificates at the Talbot County Courthouse. Two of their sons, John (27) and Levin (24), received their freedom certificates on the same day in 1814. Younger sister Grace (22) applied for her freedom papers in 1818, and brother James (21) followed her to the courthouse a few months later.19 Similarly, Henrietta and Peter Pipes sent only six of their nine adult children to register with the court clerk for freedom certificates. The two eldest sons, Perry (21) and Jacob (19), applied for certificates on the same day in 1826. The following year Peter Jr. (20) and Maria (18) appeared at the court, and finally in 1828, eighteen-year-old Eliza registered for her freedom papers. At age forty-four, Henrietta Pipes was the only one of the four parents to apply for a certificate.20

It was the young adults who applied for certificates; the elderly and children did not. Put another way, those members of the Pipes family who had no intention of leaving the Eastern Shore, including the elderly Peter Pipes Senior (fifty-four years old in 1826) and his youngest children, William, Mary Ann, and Henny Pipes (nine, seven, and five years of age, respectively, in 1826), never applied for certificates before 1833. Nor did Isaac and Memory Maccary apply for freedom papers. As the owners of a small farm of twenty-six acres, they were invested in the African American community of Talbot County and had more reasons to stay than to go.

Not everyone who applied for a certificate with the intention of leaving the Eastern Shore stayed away forever. Isaac and Memory’s son, James, applied for a certificate in 1818 when he was twenty-one years old, suggesting that he intended to follow his siblings off the Eastern Shore. But if he left, he soon returned. By age thirty-five James had married, started his own family, and was, in 1832, the head of a ten-person household in Talbot County that included his elderly father, Isaac. A survey of the freedom papers issued to African American property owners in Talbot County hints at the possibility that a number of other young men left the countryside temporarily but eventually resettled in rural African American communities. According to the 1817 Talbot County Tax Assessment, twenty-three of the eighty-one African American men who paid taxes on real estate (28%) had applied for freedom certificates. Many of them fit the profile of free African American migrants. For example, ten of the twenty-four certificate bearers were under age thirty when they applied for their certificates. More important, nine of these certificate bearers applied for the certificates before they appeared in a tax assessment. Moses Smith, for example, was born free in 1787. When he turned twenty, he applied for a freedom certificate. In 1813, at the age of twenty-six, he appeared in the tax records as the owner of a three-acre lot near the town of Easton, and he remained the owner of that lot for at least thirteen years. Perhaps Smith spent those six years between the time he applied for his certificate and the time he appeared in a tax assessment traveling and working for wages before settling on the Eastern Shore where he could be close to family and where his money would buy more property.

African Americans valued freedom papers because they potentially broadened a person’s economic and social horizons, not because they provided any meaningful protection against harassment, violence, or kidnapping. Young men and women migrated to Baltimore and to neighboring rural counties in search of work, potential spouses, or perhaps just adventure. Young people valued mobility, and not just because they were former slaves escaping the rigidity of plantation life. After all, 38 percent of the applicants for freedom certificates in Talbot and Queen Anne’s counties were freeborn. G. W. Offley, a freeborn African American, followed a path familiar to countless other young African Americans, and his migration choices exemplify the spirit of adventure among the freeborn. Offley reported in his autobiography that at twenty-one he took leave of his parents’ house in Queen Anne’s County, and “I went to work on a rail road; then I taught boxing school, and learned to write. After that I went to St. George, Del., to work at a hotel.” He traveled across the Delmarva Peninsula for six more years before moving north and settling in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1835.21

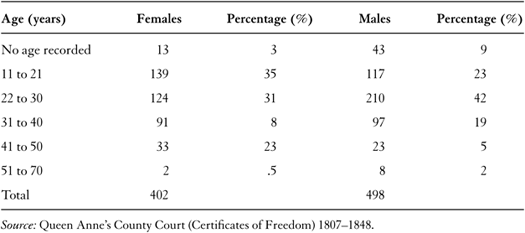

Young women were especially eager to try their fortunes in Baltimore. Women knew that neighborhood grain planters favored male over female laborers and that as long as they remained on the Eastern Shore they would be competing with slaves and freeborn child laborers to perform the least desirable, unskilled work for the lowest wages. But in Baltimore teenage girls and young women routinely found employment as laundresses, seamstresses, cooks, and domestics. Between 1810 and 1819, the number of free black laundresses included in the Baltimore directories rose from 3 to 118. By 1827 the city directory included 189 free black laundresses.22 Increased job opportunities in the city, coupled with shrinking work opportunities in the countryside, explains the steady increase in the number of country girls and women who applied for Certificates of Freedom after 1810 (tables 2.2 and 2.3). Women like Eliza Pipes, the youngest member of her family to register, made up nearly 60 percent of the certificate applicants under age twenty-one in Talbot County, and 55 percent in Queen Anne’s County.

In Baltimore and Philadelphia free African American women consistently outnumbered black men, a fact that testifies both to women’s success in the urban labor market and to men’s mobility. Young men regularly moved within the countryside, from the country to the city, and back to the country. Duplicate certificates hint at a few of these men’s experiences with circular migration. Maryland courts issued duplicate certificates to free African Americans who claimed that their original certificate was lost, defaced, or stolen. People who sought duplicate certificates at the Queen Anne’s and Talbot county courthouses often reported that the originals were lost in Baltimore. Joseph Martin, a freeborn African American, returned to the court fourteen years after he acquired his first certificate because he lost the original “while lying on the gang board, which was extended from the vessel [in which he was employed as a hand] to the wharf at Baltimore.” Martin explained that “his pocket book with his freedom papers fell out of his pocket into the dock and was never recovered.” Similarly, Jacob Gibson acquired a duplicate of his certificate after the “original was stolen with his trunk from him in Baltimore.” In 1845 Joe Boyer returned to the Queen Anne’s County Courthouse for a duplicate freedom certificate because he lost the original (issued in 1832) “while lying at the wharf at Baltimore.”23

Table 2.2 Sex and age structures of Certificate of Freedom applicants, Talbot County, 1800–34

Table 2.3 Sex and age structures of Certificate of Freedom applicants, Queen Anne’s County, 1807–34

Maryland law did not require free African Americans to apply for freedom certificates in the community in which they were born or raised: it required only that the clerk verify the applicant’s freedom either through court records (e.g., last wills and testaments, deeds of manumission) or by the testimony of a white witness. A letter sent to the Talbot County Court suggests that clerks even received requests by mail. In April 1816 Emily Green of Baltimore sent a letter to the Talbot County Court, politely requesting that the clerk “please examine the will of William Haddaway who died sometime before the War of 1812 and see if the increase [descendents] of Nelly Turner the mother, and Rachel and Airy Turner her daughters are recorded free with their increase.” She identified herself as “one of the daughters of Airy and interested in the matter.”24

Nor did the law prohibit a manumitted slave or freeborn person from acquiring a certificate in any court in the state.25 In ten years the Baltimore County Court issued sixty-one certificates to free African Americans who were born and raised on the Eastern Shore. Clerks also issued freedom certificates to Maryland-born African Americans who now lived in other states. Such was the case for Henny Barnett, a resident of Sussex, Delaware, who received a certificate from the Talbot County Court in 1807. It seems that Delaware employers accepted Maryland-issued freedom certificates as proof of freedom, giving free African Americans additional incentive to explore opportunities abroad. Maryland was not so generous. In 1831 the legislature authorized county authorities to fine employers who hired freedmen from other states.26

Joseph Martin and Joe Boyer may have returned to the Eastern Shore for duplicate certificates, or perhaps they routinely divided their time between Baltimore and the Eastern Shore. Maybe their extended families lived on the Eastern Shore, or they returned east for seasonal work. Both Martin and Boyer were twenty-two years old and freeborn when they applied for their first certificates in 1831 and 1832, respectively. We cannot be certain that the two men knew each other at the time that they first obtained certificates, but by 1845, when they sought duplicates, they surely at least recognized one another, and perhaps even traveled together to Queen Anne’s County.27 Because both men claimed to have lost their certificates at the Baltimore wharf, they probably lived in the city at least part of the year, making it odd that they would return to the countryside for a certificate that they should have been able to acquire in Baltimore. Surely after as many as thirteen or fourteen years of service in Baltimore, Martin and Boyer could have found a witness, perhaps an employer, who would testify to their freedom and save them the trip across Chesapeake Bay.

It is more likely that Martin and Boyer were part of a larger, very visible African American migration from country to city that shaped and reshaped the African American communities of Philadelphia and Baltimore. Philadelphia absorbed large numbers of African American migrants from around the Middle Atlantic region as well as from the Caribbean, and those immigrants helped create one of the most vibrant free black communities in the Atlantic world. In 1813, when the Pennsylvania House of Representatives considered legislation to ban further migration of African Americans into the state, a committee report concluded that nearly four thousand fugitive slaves had taken refuge in the city.28 In the case of Baltimore, in 1790 nearly all of the black and white residents were recent migrants to the city. In 1768 Baltimore claimed just six thousand residents, but by 1790 the population had swelled to thirteen thousand. It was the fifth largest city in the United States.29 Until 1810 the majority of African Americans living in Baltimore were slaves. Baltimore-based merchant-artisans had scoured the Maryland countryside to purchase slave-artisans in the 1790s, and planters who were narrowly focused on agriculture happily sold them. Like Maryland grain planters, these merchant-artisans wanted to maximize the profit potential of the boom in commercial agriculture by expanding their skilled workforce.

By 1810, 22 percent of Baltimore residents were African Americans, and for the first time free African Americans outnumbered slaves (5,617 free people of color, 4,672 slaves). By 1820 the free black population of Baltimore was 50 percent larger than its slave population, and in 1830 the free black population was 70 percent larger than the slave population. Such astonishing growth far exceeded both natural increase and the number of recorded manumissions in Baltimore City and Baltimore County, and it can only be explained by the voluntary immigration of thousands of free African Americans to the city. From a list of 350 African American men and women who received Certificates of Freedom in Baltimore County between 1806 and 1816, 49 percent of the applicants (171 men and women) reported that they were born and raised outside of Baltimore.30 Before 1830 nearly nine of ten black Baltimoreans were migrants to the city, and even in Norfolk, Virginia, nearly 25 percent of the free African Americans had migrated to the city from neighboring counties.31

Joseph Martin and Joe Boyer were among countless numbers of young men who came from the countryside to Baltimore and Philadelphia to work in the shipping industry. Many served as crew members on ships that took them out of the city for months at a time. In 1821 at least 284 African American men worked as mariners in Philadelphia, and 92 percent of those men were rural migrants. Thirty percent of mariners in Philadelphia came from rural Delaware and Maryland.32 Rural migrants who arrived in the city in the 1790s, when Atlantic trade was brisk, undoubtedly earned high wages for even the most unskilled labor. But African American men migrated often, and some of those male migrants may have returned to the countryside after a few months or years, moving west to work on the grain farms of southwestern Pennsylvania or northwestern Maryland. In Norfolk, Virginia, another maritime city, free black men regularly left the city to work in the countryside when the shipping industry suffered hard times. Still others went west of the Middle Atlantic region into rural Indiana and Ohio, and in the 1820s, some enterprising African American men took their maritime skills to the riverboats that cruised the Mississippi River.33

The profile of a young, single African American migrant in the Middle Atlantic states contrasts sharply with the profile of African American emigrants who left the United States for West Africa and the Caribbean. Charged with tracking the movement of former slaves out of the United States, the Maryland State Colonization Society reported to the legislature that a total of 627 free African Americans left Maryland for Africa, Guiana, and Haiti between 1832 and 1841. Fifty-one of these migrants left Talbot and Queen Anne’s counties on ships bound for Cape Palmas, Liberia, in 1835. Only six traveled alone; the remainder boarded the ships with multiple members of their immediate and extended families. The Parker family of Queen Anne’s County was representative of emigrants to Cape Palmas. The family included seven members who represented three generations, ranging in age from forty-two years (Eben Parker) to five months (Caroline Parker). Similarly, the Gibson family of Talbot County included Jacob (45) and Rebecca (43) and seven children between the ages of five and twelve. The only free African Americans to emigrate from neighboring Caroline County to Cape Palmas were the eleven members of the Walker family, including Luke (50) and Ann (35) and nine children under age fifteen.34 African Americans who emigrated from Virginia followed the same pattern of family migration to Liberia in the 1820s.35

The Cape Palmas migrants had much in common with Eastern Shore African Americans who migrated within the Middle Atlantic region. Economic opportunity, or the lack of it, for example, was a critical factor in the decision to resettle in Cape Palmas. Moreover, emigration was not a desperate act but a solution to the problem of shrinking opportunities for free African Americans. Like those who migrated within the Middle Atlantic region, the Cape Palmas emigrants expected that the move would improve their material lives. They also expected that it would benefit their domestic lives. Migration, including emigration, was one of several strategies to preserve and protect the hard-won autonomy of free African American families.